In Conversation with Dr. Karen Davis: Of Practical Applications of Trans-species Psychology, Of Demystifying Anthropomorphism, and Of The Holocaust and the Henmaid’s Tale

Today, the blog heartily welcomes Dr. Karen Davis, an animal advocate of such caliber. The blog had the privilege of first introducing Dr. Davis in the essay, The Chicken Story Retold. Dr. Davis is the founder and president of United Poultry Concerns (UPC), a non-profit organization that promotes the compassionate and respectful treatment of domestic fowl in food production, science, education, entertainment, and human companionship situations. In the last three decades of her work, Dr. Davis has made enormous contributions towards the discipline of Trans-species Psychology. Backed by empirical research data, she has written volumes about the inner world of animals in her captivating, storytelling style. This data has been used to lobby to end animal exploitation, particularly of chickens, turkeys, and other domestic fowl; and to appeal to people to recognize their shared sentience with animals.

Many in the USA today know her as the “chicken lady”, the “chicken rights advocate” who changed their lives for a more enlightened and compassionate future.

Sanctuary for rescued chickens and other domestic fowl

Through UPC, Dr. Davis runs a haven for chickens and other domestic fowl in Machipongo, Virginia. Birds being smaller than most “food” animals, are thought to be “stupid, brainless” with no personality at all, and only fit to be eaten and mistreated. This sanctuary is open to anybody who wishes to observe and feel the life of free birds from close quarters. In Dr. Davis’ sanctuary, all birds have names and her writings bring out the individuality of each. She has appeared in various radio and TV shows to advocate for them and has even pioneered a course on the role of animals in the Western philosophic and literary tradition in the University of Maryland Honors Program. She is also the author and editor of a number of important publications.

Publications and lobbying

Dr. Davis is the founding editor of Poultry Press, the quarterly magazine of United Poultry Concerns. Among its other benefits, the magazine has acted a lobbying tool for the sensitive and intelligent birds being brutalized in the name of “food”. This magazine has been chosen as one of the best nonprofit publications in North America by the alternative press, UTNE magazine.

Besides, Dr. Davis has written scores of articles and essays in various mainstream journals and magazines. To get a glimpse of the titles of her writings and the recognition bestowed upon her for her work, you can click this link on the UPC website.

Dr. Davis has written several books as well; one among the path breaking ones is Prisoned Chickens, Poisoned Eggs: An Inside Look at the Modern Poultry Industry, first edition, that focuses attention on the billions of chickens buried alive on factory farms. This book acted as a catalyst for animal rights activists to develop effective strategies to expose and relieve the plight of chickens. The second edition of the book documents the outcome of advocacy efforts since the book first appeared.

“The original Prisoned Chickens, Poisoned Eggs became a blueprint for people seeking a coherent picture of the poultry industry as well as a handbook for animal rights advocates seeking to develop effective strategies to expose and relieve the plight of chickens. This new edition tells where things stand in a new century in which avian influenza, food poisoning, global warming, genetic engineering, and the expansion of poultry and egg production and consumption are growing concerns in the mainstream population.” ~Google Books review~

Dr. Davis is also the author of a compelling academic and scholarly book entitled, The Holocaust and the Henmaid’s Tale: A Case for Comparing Atrocities, which makes the case that significant parallels can—and must—be drawn between the Holocaust and the institutionalized abuse of billions of animals in factory farms.

“Davis tackles the penultimate emblem of mass suffering, the Holocaust, and compares it successfully with the daily slaughter of millions of sentient beings in the name of human gluttony and imperialistic perfidy. Just as the claim that the 9/11 attacks in the US were more “tragic” than the slaughters in Columbia, Rwanda, Bosnia, Iraq, etc. is laughable, so too is the notion that non-human suffering cannot be compared to human suffering. Suffering is suffering, and seeking an end to same should be the goal of all reasoning beings.” ~R. Craig on Amazon.com~

Besides the above two books, Dr. Davis has also authored A Home for Henny; Instead of Chicken, Instead of Turkey: A Poultryless ‘Poultry’ Potpourri; and More Than a Meal: The Turkey in History, Myth, Ritual, and Reality.

The main points covered in this interview

In this interview, Dr. Davis explains the essence of the discipline of Trans-species Psychology and discusses its potential for positive animal rights advocacy. All trans-species psychologists employ the technique of anthropomorphism—the attribution of human characteristics to nonhuman animals—to gather data. However, this word has gathered certain taboos, not only from the animal abusers’ lobby but from the animal rights community as well. In this interview, Dr. Davis presents a holistic understanding of “anthropomorphism” by making a distinction between false anthropomorphism and empathic anthropomorphism. She points out how anthropomorphism of the false kind is used by animal abusers to destroy the dignity of animals. Conversely, she points out the enormous value of empathetic anthropomorphism and how the latter is used for positive animal rights advocacy.

In the penultimate section of the interview, using the metaphor of the Holocaust, Dr. Davis makes a case for the similarities in the psyche of the oppressor—whether it be humans abusing animals or humans abusing other humans—and the similarities in treatment meted to the victims – whether human or nonhuman animals. Dr. Davis leaves us with a bibliography of important books and blog sites under the discipline of Trans-species Psychology.

|

| Dr. Karen Davis at her desk in the office of United Poultry Concerns |

Vegan India!: Dr. Davis, first of all many thanks for consenting to this interview with Vegan India! blog. We understand that the research on the emotions and cognitive capabilities of animals, particularly chickens, done by your organization, United Poultry Concerns, and cited in your books belong to the discipline of “trans-species psychology”. Could you please share your insights based on your experience on the potential of this discipline for positive animal rights advocacy? What are the takeaways from this discipline for animal rights advocates that one can implement effectively to change the way animals have been objectified in our culture?

Dr. Davis: Humans share evolutionary kinship with other animals, yet many people continue to resist acknowledging our common heritage and inter-subjective ties with other species. Animal advocates seek to overcome this resistance by stressing our shared sentience. Pain and fear in particular have been emphasized given that animal advocacy is a response to the abusive relationships that humans have established with other creatures, abuses rationalized on bases that deny subjectivity and consciousness, hence moral worth and ethical claims, in beings who are not human.

In the 20th century, Western science defined other animals almost exclusively in terms of “drives” and “instincts”. “Fear” and “aggression” dominated the discourse. Rigid behaviorists still insist that other animals do not have subjectivity, or that the study of emotions and consciousness in them is futile, because psychological states cannot be empirically tested in other species. The naturalist Joe Hutto who said of young turkeys he raised that on seeing him at dawn, they did “a joyful, happy dance, expressing an exuberance,” would be ridiculed by the strict behaviorist as a sentimentalist projecting his own feelings and desires anthropomorphically onto these birds rather than “objectively” describing their behavior as, perhaps, “dance-like locomotion,” and letting it go at that.

For 22 years until she died, I had a beloved parrot companion named Tikhon. I used to marvel over the fact that she and I knew each other so well, that we were so close and communicated so intimately without ever having “talked about” a single subject. We shared experiences that could only have happened through the medium of our relationship with each other. As an advocate for chickens and turkeys, I observe and interact with the birds at our sanctuary every day, and I make it my business to evoke their lives through storytelling as best I can. People are fascinated and affected by the stories I tell, which enlighten their view of these birds to an appreciation of the fact that chickens and turkeys have personalities, expressiveness, emotions, cognition, and empathy.

|

| Mavis and Karen |

For example, I tell people the story of a shy and timid hen we adopted once named Mavis, who, after coming to our sanctuary, stayed alone by herself in the yard, seemingly uninterested in the other chickens or in me. One day I looked up from hugging our three “broiler” hens, who would urge me every day by bumping up against me with their chests, to crouch down and embrace them all together as a group. Thus engaged that day, I saw Mavis standing stock still and staring at us. Struck, I thought: does Mavis want to be hugged? I withdrew from the three hens, walked over and knelt beside Mavis and pulled her gently toward me. There was no resistance at all. She rested against me so comfortably and completely that I felt as I held her close and stroked her feathers that this was exactly what she had wanted me to do.

My experience with chickens and turkeys since the mid-1980s has shown me that these birds are conscious and emotional beings who can relate empathically with one another and with me. I tell people about the time that my hen, Sonja, walked over and nestled her face next to mine when I was crying and deeply upset. I don’t know whether Sonja knew why I was crying, but there is no doubt in my mind that she knew I was sad and sought to comfort me. She comforted me with an expression of empathy that I have carried emotionally in my life ever since. These kinds of experiences, these stories of mutual responsiveness and understanding, traverse species boundaries and dissolve them in the deeper moments of our lives, revealing humanity’s psychological ties with other creatures.

I regard well-told personal accounts, like my stories of Sonja and Mavis, to be crucial to effective animal advocacy, especially when it comes to animals such as chickens and turkeys, who have been misrepresented as having few or no feelings or consciousness, who are said by those who mistreat them for profit or pleasure to lack the ability to be companion species. These bogus claims can and must be challenged with truthful stories showing otherwise. A story describing a significant encounter with a fellow creature of another species is one of the best ways to reach people.

Vegan India!: This brings us to the topic of anthropomorphism as a lot of the “affective” material in trans-species psychology is derived from it. In your writings, you have made a distinction between “false” anthropomorphism and “empathic” anthropomorphism. We understand it is false anthropomorphism that animal rights activists need to be cautious of; empathic anthropomorphism, on the other hand, is the most natural and logical method of building data since we recognize our kinship with the animals. Dr. Davis, could you please explain the distinction between false anthropomorphism and empathic anthropomorphism for our readers with some examples? Also, how is false anthropomorphism used by animal exploiters and how can empathic anthropomorphism be used by animal rights advocates for positive animal rights advocacy?

Dr. Davis: Once in the 1970s when I was living in San Francisco with my parrot Tikhon, I visited a wild bird rescuer whose house was filled with injured owls and other birds he was rehabilitating. The rescuer cared about these birds, yet he rejected any suggestion that birds and humans could relate to one another psychologically or emotionally. Nothing I told him about my relationship with Tikhon would change his mind. To him, all of my interpretations of her feelings, desires, and intentions were “anthropomorphic” – an imposition of my personal desires and wishes onto her. He seemed to combine the belief that birds don’t have an interior life with a belief that whatever interior or trans-species experiences they might be capable of having, are unverifiable and are therefore as good as nonexistent. I felt that his natural affinity for birds had been overridden by the 20th century behaviorist taboo against “anthropomorphism” – the attribution of human characteristics to nonhuman animals. (Originally the term referred to the attribution of human characteristics to a deity.)

In 2004, while reading the transcript of a talk by an agriculture professor in Iowa who argued that the animal rights movement attracts people with “anthropomorphized visions of animals,” I thought: Animal rights advocates are not the primary “anthropomorphizers” of nonhuman animals: animal exploiters are. Institutionalized animal abusers are the ones who impose human traits and desires onto other species, rhetorically and materially, in order to justify mistreating them. It is they who will go so far as to insist that the animals they otherwise treat as objects want to suffer and die for humans. They say such things as: dolphins are happier in amusement park tanks than they are in the ocean because in captivity they receive three square meals a day. They falsify roosters as “wanting” to act out human aggression in cockfighting rings (but to liberate this purported desire in roosters they have to be punished into a state of psychological trauma). It is animal exploiters who dress up carriage horses in clownish costumes and force elephants and tigers to enact human notions of entertainment that have nothing to do with the natural behavior and choices of elephants and tigers. Animal abusers are the ones who genetically reconstruct chickens’ and turkeys’ bodies to reflect and satisfy human dietary and monetary desires, then cynically assert that the debilitated birds are healthier and happier than normal chickens and turkeys. The list goes on. Imposing human desires on other animals against their will, claiming they are “happier” in zoos than they are in “the wild” (their own natural homes) is the essence of false anthropomorphism, which also includes unhealthy pet-keeping situations in which the “pet” is forced to mirror the owner’s self-centered desires pathologically.

|

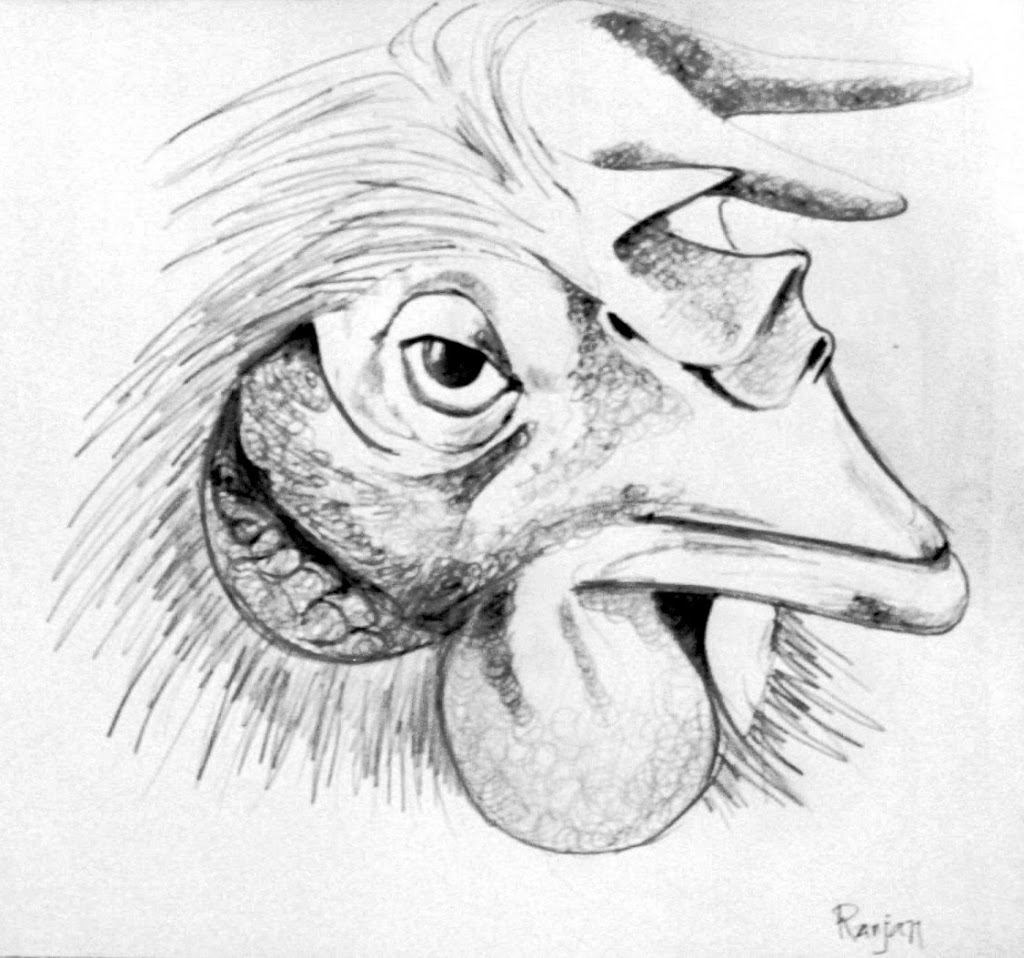

||||||||||

| “What must be we do to prove we are ‘persons'”? Illustration courtesy: Nature’s Chicken by Nigel Burroughs |

My vision of false anthropomorphism has an apt metaphor in the mythological bandit Procrustes (“the stretcher”), who in classical literature keeps an iron bed to which he forces his victims to conform. Watching them approach his stronghold, he stretches or shrinks the bed to predetermine their failure to fit into it so that he may torturously reshape them to suit his will. If the victims are too tall, he amputates their limbs; if they are too short, he stretches them to size. Procrustes is a fit symbol of the false anthropomorphism people use to force nonhuman animals into constructions that are fundamentally alien and inimical to them. When the wishes and desires of the human psyche conflict with the needs and desires of other animals, a Procrustean solution is devised whereby the animal is either cut down to size or stretched to fit the agenda. Animals are physically altered, rhetorically disfigured, and ontologically obliterated to mirror and model the goals of their exploiters.

False anthropomorphism entails maintaining the illusion that humans and other animals are separate orders of existence (“I am a subject, you are an object.”) while simultaneously maintaining that other animals are willing participants in being disfigured to accommodate human interests.

The opposite of false anthropomorphism is empathic anthropomorphism, in which a person’s vicarious perceptions and emotions are rooted in the realities of evolutionary kinship with other animal species in a spirit of goodwill. I stress that my view of false anthropomorphism versus empathic anthropomorphism entails attitude as well as action, goodwill versus ill will. (I stress this because empathy can be employed harmfully as well as compassionately toward others.) In general, though, according to my definition, false anthropomorphism is rooted in, and facilitates, emotions of hostility to animals. The goal is to oppress the animal and the animal’s identity into compliance in order to serve the human interest at the expense of the animal’s own interest. Empathic anthropomorphism by contrast is rooted in emotions of fellowship and respectfulness toward an animal or animal species. Through these emotions, aided by careful observation, reasonable inferences may be drawn regarding the meaning of an animal’s body language, vocal inflections, and other less easily characterized expressions.

For example, when a chicken is feeling ill, her (or his) condition is reflected in a drooping posture and woeful tones of voice. A rooster with an illness who has been removed from his flock and the yard where he lived exuberantly in his better days will stand on the porch at our sanctuary and focus obsessively on what is going on outside with his companions. He will pace back and forth and circle back to that spot where he stands looking out upon his world with what can only be described as yearning frustration. Possibly he feels frustrated not only in being apart from his companions and his place, but in being prevented from actively influencing what his friends are doing out there.

Happy chickens are audibly and visibly vibrant, cheerful, and eager. Their eyes are bright, their posture is alert, their voices are alive with the emotions they’re experiencing in expressing their nature as chickens in an environment that answers to their interests – digging in the earth through fallen leaves, basking in the sunlight, settling contentedly together on their perches at night, exercising their ability to make choices throughout the day. I marvel at how cheerful chickens are in all kinds of weather, rain, snow, or sunshine. The contrast with their disconsolation when they are sad or bored or helplessly afraid is unmistakable. Virgil Butler, who worked for years in a Tyson chicken slaughterhouse, described how the chickens hanging upside down on the slaughter line would try to hide their poor little faces in the feathers of the birds beside them, and how scared their eyes were.

Vegan India!: Another related topic is how animal rights advocates have often used to make a point by drawing parallels with the holocaust brought about by the Nazis. Matt Prescott, the creator of the “Holocaust on Your Plate” campaign has written that the “comparisons to the Holocaust is undeniable and inescapable…. because we humans share with all animals our ability to feel pain, fear and loneliness….” However, there are opposing views in using the metaphor of the Holocaust to describe the human manufacture of animal suffering in today’s context because the “Holocaust is sacralized, and comparisons are perceived as blasphemy”. (Boria Sax, Animals in the Third Reich). Dr. Davis, in your book, The Holocaust and the Henmaid’s Tale, you have made a convincing case in favor of the comparison. Please tell us the primary reasons why the human-engineered extermination of six million people in the Holocaust is comparable to the human-engineered oppression of animals happening every day?

Dr. Davis: As I explain in The Holocaust and the Henmaid’s Tale: A Case for Comparing Atrocities, I believe that significant parallels can be drawn between the Holocaust and the institutionalized abuse of billions of nonhuman animals, and that there are lessons to be learned by viewing each of these evils through the bleak lens of the other. The reduction of a sensitive being to a nonsentient object links the Holocaust victim to the animal victim in laboratories, factory farms, and slaughterhouses in ways that diminish the differences between them. Heinrich Himmler, the brutal chicken farmer and Nazi executioner, exemplified the pitiless spirit of human and nonhuman animal exploitation. He said, “What happens to a Russian, to a Czech, does not interest me in the slightest…. We shall never be rough or heartless when it is not necessary…. But it is a crime against our own blood to worry about them”. His statement captures the mentality of animal abusers toward their defenseless victims.

The Holocaust epitomized the attitude that we can do whatever we please, however vicious, if we can get away with it, because “we” are superior and “they”, whoever they are, are, so to speak, “just chickens”. While the word “Holocaust” represents a unique historical phenomenon of the mid-20th century, the term can transcend this phenomenon to function more broadly on behalf of a more enlightened and compassionate future. A broader approach allows a more just apprehension of past and present atrocities by connecting the Holocaust to the larger ethical challenges confronting humanity. Interestingly, the word holocaust is neither species-specific nor culture-specific. The term was taken over from the Greek word holokauston, meaning “whole burnt offering”, which in ancient times denoted animal sacrifice. To those who complain that the word Holocaust is being falsely appropriated to characterize the experience of nonhuman animals at the hands of humans, I suggest that the original holocaust victims have every right to complain that their own experience of being forcibly turned into burnt offerings (and to please and sate a god they would not necessarily have acknowledged as their god) has been appropriated by their victimizers, who are robbing them of their original experience of unjust suffering.

|

| Poster courtesy: Truth Exposure |

In conclusion, although I have much more to say in The Holocaust and the Henmaid’s Tale, there is precedent for contextualizing the word holocaust to include the animal experience that Charles Patterson describes unforgettably in his book Eternal Treblinka. The United States Holocaust Museum states in its guidelines for teaching about the Holocaust that, “The Holocaust provides a context for exploring the dangers of remaining silent, apathetic, and indifferent in the face of others’ oppression”. Nonhuman animals are “others” no less than we humans are; they have faces and feelings and families the same as we do. If it is wrong to treat other human beings like “animals”, it is no less wrong to treat other animals like “animals”. We have the capability to do better. We need to nourish, develop, and cherish this capability and by doing so, to exterminate the fascist within us.

Vegan India!: Dr. Davis, in the end, could you please suggest books or other materials on the discipline of trans-species psychology.

Dr. Davis: Here is a short selection of resources.

Books

Karen Davis, Prisoned Chickens, Poisoned Eggs: An Inside Look at the Modern Poultry Industry. New York: Lantern Books, 2009.

Karen Davis, The Holocaust and the Henmaid’s Tale: A Case for Comparing Atrocities. New York: Lantern Books, 2005.

Karen Davis, More Than a Meal: The Turkey in History, Myth, Ritual, and Reality. New York: Lantern Books, 2001.

Experiencing Animal Minds: An Anthology of Animal-Human Encounters, ed. Julie A. Smith & Robert W Mitchell. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012.

Annie Potts, Chicken. London: Reaktion Books, 2012.

Sister Species: Women, Animals, and Social Justice, ed. Lisa Kemmerer. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2011.

Critical Theory and Animal Liberation, ed. John Sanbonmatsu. New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2011.

Minding the Animal Psyche, Spring: A Journal of Archetype and Culture, Volume 83, ed. Nancy Cater & G.A. Bradshaw. New Orleans, Spring 2010.

Mark Bekoff, The Animal Manifesto: Six Reasons for Expanding Our Compassionate Footprint. Novato, CA: New World Library, 2010.

G. A. Bradshaw, Elephants on the Edge: What Animals Teach Us about Humanity. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

Tina Volpe & Judy Carman, The Missing Peace: The Hidden Power of Our Kinship with Animals. Flourtown, PA: Dreamriver Press, 2009.

Charles Patterson, Eternal Treblinka: Our Treatment of Animals and the Holocaust. New York: Lantern Books, 2002.

Animals & Women: Feminist Theoretical Explorations, ed. Carol J. Adams & Josephine Donovan. Durham: Duke University Press, 1995.

Margaret A. Stanger, That Quail, Robert. New York: HarperPerennial, 1962; rpt. 1992.

Loren Eiseley, The Immense Journey: An Imaginative Naturalist Explores the Mysteries of Man and Nature. New York: New York: Vintage Books, 1946; rpt. 1959.

Blog & Website Resources

Thinking Like a Chicken. United Poultry Concerns. http://www.upc-online.org/thinking

G. A. Bradshaw, Bear in Mind. Psychology Today. http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/bear-in-mind

Marc Bekoff, Animal Emotions. Psychology Today. http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/animal-emotions

Chicken Run Rescue. http://chickenrunrescue.org

Free From Harm. http://freefromharm.org

Matilda’s Promise, Eden Farm Animal Sanctuary.

Vegan India! http://vegan-india.blogspot.in

VINE (Vegan Is the Next Evolution). http://www.bravebirds.org

Thank YOU, Karen, for everything you do to honor these precious sentient beings and to educate the world on the value of all life. Blessings!! Maureen

Thank you Arun, really glad that you like the interview. Indeed, the knowledge about the inner lives of these sensitive birds is both fascinating as well as it breaks the heart to think about how they are used and abused.

Thank you so much, Vegan India and Dr. Davis for such a moving interview. My heart felt very heavy after reading this – particularly after learning how terrified chicks attempt to hide their faces behind others' faces.

At the same time, I'm so touched by Dr. Davis' work, and her experiences with her bird friends. Vegan India, you are doing such a wonderful job, and Dr. Davis' recommendation says it all!

Dear Dr. Davis,

We are immensely grateful to have had the chance to speak to you to learn more about the discipline of Trans-species Psychology and its potential for positive animal rights advocacy. Thank you so much for your time. Your work is among the finest examples of how academics, research, and the practical applications of theories can blend and create synergy to produce rich grassroot-level interventions for the dear animals. Thank you so much.

Thank you so much for inviting and posting this Interview with me on behalf of chickens and turkeys and all other precious creatures with whom we share life, feelings, friends, family, and intelligence. Let us hope and work for a better life for all Beings in 2013 and beyond.

Karen Davis, PhD, President, United Poultry Concerns