Indhrivanam: A Vegan Homestay in Kerala, and An Interview with the Host Morten Aagren

Article by Dr. Arun Rangasamy and Uthra

In June this year, we were looking for a vegan-friendly homestay not very far from Bangalore to spend a weekend peacefully, and when we found Indhrivanam in Kumily, Kerala, we were a bit surprised to know that the meals served in the cottage is vegetarian, and the cottage can accommodate vegans (Kerala is known for its meat-heavy culture, although most traditional vegetarian dishes of Kerala are actually vegan).

After going through their very well designed web-page, we got in touch with the host Morten to confirm if we can get vegan food at Indhrivanam. This is when our surprise of encountering an explicitly stated vegan-friendly accommodation turned bliss. For, Morten informed us that he and his wife Sarah are vegans! There are very few exclusively-vegan accommodations in India, and it was kind of a ‘Eureka!’ moment for us. We could not wait to visit Indhrivanam.

However, Morten was a bit wary, and warned us that June might not be the best month to visit Indhrivanam due to the monsoon, which can potentially wash out our plans, and pointed out that Indhrivanam is a little different from other places (for instance, Indhrivanam is built on sound ecological principles, including relying only on rainwater to meet their water requirements, usage of dry-toilets to conserve water, etc). Morten also graciously offered to refund if our trip is washed out, or arrange for an alternative accommodation (should we wish). We re-assured Morten that we were fine with the monsoon-risk, and were actually looking forward to learning something on sustainable living from them.

There are a few direct buses from Bangalore to Kumily, including some sleeper buses, but we deferred booking tickets till two days before our planned departure. As it turned out, the weather was pleasant till the Wednesday before our journey (planned for a Friday), but return tickets to Bangalore in sleeper buses were not available then. So we booked a bus from Madurai to Bangalore. Madurai can be reached from Kumily in about 3 hours, and Morten informed us that there are plenty of buses from Kumily to Madurai.

Our bus to Kumily reached Kumily at around 8:00 AM. The stretch from Cumbum (about 25 km before Kumily) is a teaser to the ravishing beauty of Kumily and Indhrivanam, and we were glad we were awake, and could enjoy it. Kumily is a slightly unusual town – a part of it is in Tamil Nadu and the rest of it is in Kerala, and the difference is too prominent to be missed (for instance, the kinds of restaurants and shops across the two sides of the border).

Morten had requested Raju (a permanent employee at Indhrivanam) to facilitate our transfer to an auto-rickshaw that would take us to Indhrivanam from Kumily bus-stand. Thanks to Morten and Raju, we could get a cozy auto to Indhrivanam at a compelling price without the need for negotiating in Malayalam.

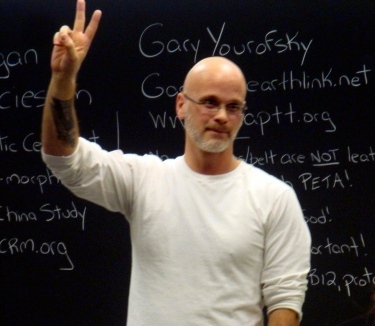

Figure 1. Morten, Ashna and Sarah (From Left)

Morten and Sarah gave us a warm welcome, and introduced us to Ashna, their lovable, mild-mannered canine companion. Like most vegans, we were excited to get introduced to fellow vegans, and within minutes of interaction, we realized how friendly and pleasant hosts they are. We were awe-struck by the look of the house built with rocks, amidst the lush vegetation. However, the best was yet to come.

Morten and Sarah took us to the cottage. The path to the cottage was etched with rocks, with lovely plants and majestic trees on the sides. The cottage is the most beautiful place we have ever stayed. Built like the main building using rocks, the cottage is the lone building in a mini-forest full of huge, tall trees of various kinds (The main building is a couple of minutes’ walk away from the cottage, but it is not visible from the cottage). The suspended wooden chair just beside the entrance of the bedroom in the cottage is a perfect match to the peaceful ambience.

As the hosts explained us about the features of the cottage, we realized that every bit of the cottage is designed aesthetically, and at the same time, taking utmost care to minimise the impact on our environment – for instance, the cot is made of cane; the pleasing sliding windows are made of locally available wood; the hygienic dry toilet with health faucet significantly cuts down the requirement of water; the fragrant liquid soap is vegan and bio-degradable. In addition, the cottage has wi-fi facility, and has provisions for making coffee and tea.

We soon figured out that Morten and Sarah are ethical vegans, and were over-joyed on knowing this. We found it very hard to see them off, even though it was only a matter of tens of minutes before we would join them for break-fast. Finally, after several attempts, we let them go and make break-fast. We knew by then that there wouldn’t be enough time for us to talk, for it seemed as if there were endless queries to ask them, and topics to discuss with them.

Soon afterwards, we joined them for break-fast at the main building. Sarah had made poories with delectable channa masala, which went very well with the poories. We were pleasantly surprised to realize Sarah’s mastery over Indian spices, as we relished the flavourful breakfast at the fixed dining table made of rocks.

Our conversation with the hosts seemed to go on for ever, as we discussed how they became vegans and ended up in Kumily (details in the Interview section), the design of the buildings in Indhrivanam (both the main building and the cottage), their lifestyle choices, how they found Ashna, and so on. As we discussed, we could see their commitment to protecting our environment.

Morten had done quite a bit of reading before designing the construction of the buildings in Indhrivanam, the electrical wiring, choosing the type of materials to be used, managing just with rain water, … Since the design of the buildings is unconventional, they did not have many local experts, and had to make several decisions themselves. While constructing the buildings, they made every conscious effort to reduce the impact on the environment, minimizing the use of concrete and trying to make use of locally available materials whenever possible.

They are very much opposed to cutting trees, and point out that protecting our environment is in the interest of non-human animals as well, as they are some of the least privileged beings, and the most affected by climate change. Incidentally, no tree was cut to make room for the cottage construction (when they bought the property, there was a cow shelter at where the cottage is, now). The fixed dining table is made of stone, and wood used is of the non-indigenous (Australian) silver oak variety, which is unloved by the local population of birds and insects, and absorbs very small amounts of CO2.

Morten and Sarah make the most of the rains, and meet all of their water requirements just from rain water (no borewell, well, corporation/municipal water, etc). They have constructed a huge underground storage tank capable of holding more than 1 lakh litres of water in their land across the road that separates that land from the campus where they stay, and direct filtered rain water to this tank. We were dumbfounded, when we came to know later that water is manually pumped from this underground water tank across the road to the overhead tank in the main building using a pressure treadle pump; it will pump up to 3000 litres of water over huge distances and up gradients. When in need of water, Sarah takes a book with her, and keeps stepping on the foot-pump as she reads.

In addition to conserving rain water, the hosts manage whatever water they have, judiciously. To that end, they have limited the capacity of the water heater in the bathrooms, and use hygienic western style dry toilets, which are incredibly easy to use, with health faucets. In the dry toilet they have, solid and liquid wastes are separately collected. Solid waste goes into an invisible bucket layered with saw dust. After using the toilet, the waste is completely covered with sawdust. By ensuring that the waste is completely covered, and that the solid and liquid wastes do not mix, the toilet is completely free of unpleasant odour. Using this is very similar to dumping kitchen wastes into a composter which has alternating layers of remix powder (eg. compost or saw-dust) and waste – only that, the ‘remix powder’ (sawdust, here) is used generously.

As we wanted to get a first hand experience in managing dry toilets, the next day (Sunday) we volunteered to empty the collected waste-sawdust mixture from the cottage to the designated area (after convincing the hosts) – the hosts (Morten/Sarah) do this otherwise. The place was free of odour (we compost our kitchen waste that feeds our veganic micro-garden at home, and so we were not surprised), and dumping and cleaning the bucket holding the collected waste was again, incredibly easy.

We did not have plans to see places around Kumily, as we were there just for the weekend (Quite frankly, we did not have enough time to interact with the hosts, who by the time we left, probably had enough of us, even though we spent most of our time at Indhrivanam with the hosts). There are plenty of places to see, though (Morten can help with that). However, we went out for a short walk of about a couple of hundred metres, to observe the plains of Tamil Nadu from the heights of Kumily (if one is thrilled to look at the photo at www.indhrivanam.com, that is nothing to enjoying the breath-taking view of the plains directly), and the neighbourhood of Indhrivanam, which had a lot of coffee and cardamom plants.

On Sunday, we took a short stroll through Indhrivanam’s mini-forest, and then we realized how different Indhrivanam is from the neighbourhood. But for the two buildings (the main building and the cottage), most of the land in Indhrivanam, is covered by trees. We did not know what species they were – although there were some unusually (naturally?) tall mango trees, with at least a dozen mangoes on the ground (and we had to resist the temptation of picking them up, as Morten had informed us of the non-human animal inhabitants of Indhrivanam, who might find them useful).

Through the nearly two days of our stay in Indhrivanam, we were treated to a variety of dishes from different cuisines, thanks to Sarah. For one meal, we had yummy Kerala style bitter-gourd thoran, beans poriyal and koottu; for another lunch, we had saffron flavoured vegetable pulav with the freshest- cashew-cream infused cauliflower and thohaiyal. We also relished our all-time-favourite Adais and chilkas. Every single dish was pleasantly aromatic, thanks to Sarah’s magic using the rich spices and coconuts of Kerala.

We were planning to buy spices from Kumily before leaving, and the hosts helped us find top quality spices and fresh, creamy and un-split cashews at low price (Sarah offered us samples from her kitchen – we realized how rich and flavourful they are, in contrast to the ones we find in Bangalore). A good news for those who cannot visit Kerala anytime soon – we can order them online from www.spicekada.in.

With lasting memories of our stay and gratitude for the hosts (for their hospitality, responsibility, respect for nature and animals, exemplarily vegan lifestyle, …), we bid adieu to Morten, Sarah and Ashna on Sunday evening, hoping to come back as soon as possible (The hosts had arranged for an autorickshaw to take us back to Kumily bus-stand).

Here is our interview with Morten (To make sure that we don’t unintentionally modify anything, we requested for an email interview, for which Morten kindly agreed):

1. People go vegan for health, environment or for animals. What is the primary motivation for you to become vegans?

In addition to ethical, environmental and health vegans, we have met spiritual vegans (a semi to wholly religious belief that all beings are sacred) and medical vegans (who may have been brought up as vegetarians and consequently cannot digest meat, and, in addition, may be dairy intolerant).

I (Morten, who is writing most of these uncharacteristically unhumorous replies as I am the long suffering typist. However, Sarah and I are in agreement about most things vegan) grew up in Denmark, a country where 99% of the population is non-vegetarian, and the average person consumes 120 kilos of meat per year. Sarah grew up in the UK where being vegetarian is more common, and, consequently, there is less stigma attached to being vegetarian. In practical terms, it was much easier, even a couple of decades ago, to be a vegetarian in the UK than in Denmark. Partly, I think, because there was a much greater influence from Asian cuisines in the UK.

I became a vegetarian in 1991, at the age of 21, but was never a 120 kilos of meat per year kind of person before becoming a vegetarian. I would eat meat once or twice a week, probably 10 kilos in total per year. As I found the taste of meat disgusting from as early as I can remember, I could, of course, have chosen to become a vegetarian at lot earlier, but the meat culture in Denmark, then and now, is very strong, and it never occurred to me that it was a feasible option to remove meat entirely from my diet.

The impact of the meat culture on Sarah was so strong that even though she had signed petitions against vivisection, cosmetic testing on animals and the wearing of fur, she still ate meat until 1992. She became a vegetarian while doing voluntary work where quite a few people were vegetarian, and she started thinking about their reasoning.

5 years after Sarah and I met, in the year 2000 while living in Denmark, our home became vegan. It came about when Sarah, while cycling home in Copenhagen, passed a window with a poster for the Danish Vegan Society (there can’t have been many members. Addendum: I just visited their homepage. It says “last updated in 2005”). She read up on reasons to go vegan, and that was the life changing moment. I would still consume some dairy products at work for a couple of years because of the non-existing vegan food in the canteen.

We are ethical vegans, i.e. we believe that any exploitation of any animal is wrong. This, of course, includes humans, which means that we see anti-capitalism as an integral part of promoting veganism. Only by removing all aspects of exploitation and injustice from society will it be possible for the human to consider not exploiting animals. Ensuring that pollution is minimised and, on a global level, that CO2 emissions are lowered, are crucial parts of being vegan as the deterioration and destruction of the natural environments lead to the suffering and death of animals. Incredibly, we are in a period of mass extinction of species, and the responsibility is that of one species only: the human.

For us, the solution is that, in addition to being vegan, we try to minimise our consumption in order to reduce our impact on the environment. This means that we consider very carefully the necessity of buying consumer products, and, whenever possible, we buy these second-hand.

2. Most vegans alive today would have consumed animal products at some point in their lives, till they became aware of, or related to animal suffering. How did you become aware of, and relate to animal suffering?

For me, the concept of justice has always been an overriding principle in my life. When I was young, the concern was with humans. Even though I lived in one of the most equal countries in the world, there were still significant differences in salaries between workers and owners, and between women and men. In addition, and very importantly, a lot of people had very little power over their own lives. In my mid-20s everything finally fell into place, and the realisation that the most exploited and suffering creatures were actually farm animals, led to the natural consequence that taking part in this had to stop.

3. What was your family’s reaction when they came to know of your decision to go vegan?

We both became vegetarian and later vegan after leaving our family homes, so it had little to no impact on our families. In my family, there has always been a lot of freedom, and Sarah’s is a family of vegans and vegetarians, so the concept of veganism wasn’t hard for them to comprehend.

4. How did you choose to settle in India, and set up Tiptoe Travel and Tourism?

You have one life. Sometimes you create or are given the chance to do something different. There are gurus who have lived their entire lives in a cave, there are people who decide to dedicate their lives to helping humans in war zones, and some who decide to rescue animals. We are a lot more modest. Our initial reason for leaving Europe (in 2007) was to get out of the restraints of the system. We succeeded, but have simply entered a different system, with different rules, duties and obligations. The positive aspect is that our company, Tiptoe Travel and Tourism Pvt. Ltd., owns 1.6 acres of property in the Western Ghats, the location of our resort homestay, Indhrivanam, where we can prevent trees from being cut, and increase the bio-diversity on the property. The deforestation of the Kerala high ranges is a huge problem, not only for bio-diversity, but also for the climate. Since independence, approximately 20 crore trees have been cut in Kerala, and the rainfall in the high ranges is a lot less than it used to be, and average temperatures have increased significantly.

The consequence of not cutting trees is that we have continuous tree cover on the property, and we have several slender lorises, an endangered primate indigenous to South India and Sri Lanka only, living on the property. They are arboreal and only live in places where they can move from tree to tree. You won’t find these anywhere else in this area in such close proximity to humans.

With Indhrivanam (indhrivanam.com), we can offer something that is quite a lot different from any other tourist accommodation in the Thekkady area. For instance, our location is close to tourist activities (8km), yet away from Kumily Town where most of the tourist accommodation is; the property is organic with no use of chemicals; Indhrivanam is probably the only purely vegan accommodation in Kerala; and we try to employ sustainable practices, e.g. our water supply is entirely from our rainwater harvesting system, and we use only dry toilets to save water, create compost and maximise hygiene.

5. Besides Indhrivanam, what other services does Tiptoe Travel and Tourism offer?

The second part of the company is Simply Kerala (simplykerala.in) which is a more conventional, small scale tour operation with the purpose of arranging holidays in Kerala and parts of Tamil Nadu. And we arrange a half-day trip in the Thekkady area into Tamil Nadu where people can experience temples, farming and traditional Tamil food.

6. Are guests curious about the design and construction of Indhrivanam?

It varies. Our experience is that most people are interested, primarily, in themselves. For instance, we get surprisingly few questions about how it is to live in a village in the mountains of South India, which, potentially, is an interesting question. And that is fine with us. After all, it is a lot easier to arrange a trip to a spice garden than it is to analyse and share your analysis of your own lives.

Occasionally, an architect or engineer passes through, and they do ask a few more questions about constructing, but the principles we have applied are quite different from mainstream principles, i.e. our walls, floors and tables are made of rock, there is limited use of concrete, and no teak trees have been cut in the creation of the buildings. Any self-respecting Keralite will cut a teak tree to make a door with intricate carvings. These days, teak wood is imported from South East Asia as all teak trees in Kerala suitable for furniture, doors and frames are long gone; cut and consumed. Instead, we have used sustainable wood for the doors, i.e. non-indigenous trees that absorbed very small amounts of CO2 before they were cut.

7. We enjoyed sumptuous and flavourful food during our stay. How did you master Indian cooking?

You experienced Sarah’s cooking. I can cook, but whereas I enjoy eating tasty food, I don’t get pleasure from cooking. Sarah does, so she cooks for guests when required, and sometimes our employee, Raju, will do the cooking. They have different strengths and weaknesses in their cooking repertoire and, hence, will be in the kitchen at various times.

As with all skills, it is talent, knowledge, hard work, experience, and an openness to new ideas that are important. So, even though it is not easy to cook Indian food at a high level, Sarah usually gets it right. Recipe books, websites and experience from our local friends is part of the reason for the success.

8. Do guests appreciate the vegan food available at Indhrivanam?

Food preferences are not important when staying at Indhrivam as all stays are on EP (excluding food). People can pay for vegan food if they want to eat on the premises, or they can eat out if they prefer. There are tourist hotels 4 and 10 kilometres from Indhrivanam that will serve anything at any budget. We call the food we serve Indian vegetarian in order to not create confusion or frighten the conservative types, but it is vegan.

Our most common bookings are for 2 nights, and people will usually eat breakfast and one or two additional meals. I think the consensus is that the food is very good. But we do have guests who have to eat meat in order to feel comfortable, and for whom eating a meal without meat is impossible. We will advise and recommend other places to eat at.

9. We see that that farming is not actively pursued in Indhrivanam (in contrast to neighbouring areas that have a lot of cardamom, coffee or pepper plants). You also have plenty of veganic fertilizer, thanks to your composting all bio-degradable waste. Is this a conscious decision? If so, why?

There are two main types of farming: cash crop farming and subsistence farming. Where we are, the vast majority of farming is cash crop farming, which are the crops you mentioned. The first reason for not growing these is that it is illegal, which makes any other reason irrelevant. As foreigners, we are not allowed to engage in growing and selling produce in India because it would compete with Indian farmers. If we started selling cash crops we would be in violation of our visa conditions, and would risk a ban from entering India. This would, obviously, not be good. We do, however, grow Arabica and Robusta coffee for our own consumption (15 kilos per year), and we grow enough pepper and cardamom for our own household. Secondly, most cash crops are grown with the use of pesticides, and no chemicals are allowed on the property. Third, our concern is and always will be, animals, plants and trees, and most cash crops will turn any property into a place that doesn’t encourage bio-diversity. Consequently, we would always encourage forest over crops.

Subsistence farming is quite difficult in our area. There is a reason that the primary diet of the locals used to be tapioca, yams, chillies and green bananas: nothing else would grow. The weather is quite unpredictable, and just that little bit too tropical, which makes the growing of, for instance, garlic, onion, carrot, and cabbage, difficult. In Munnar, 70 km north of Indhrivanam, at 1600 metres elevation (we are at 1100 metres), those vegetables can be grown.

However, considering the size of the property, we do have a significant number of fruit trees. The total is around 250 jack fruit trees, 20 mango trees, 10 orange and mandarin orange trees, 10 coconut trees, 3 avocado trees, 3 lime trees, 2 apricot trees, 1 fig tree, 2 sapota trees, 1 pomegranate tree, 2 star fruit trees, a few rose apple trees, goose berry trees, guava trees, banana, papaya, all the ones we haven’t spotted, plus various berries and climbers, for instance passion fruit. Many of these haven’t yet started fruiting as they are young. The bulk of the fruit is left on the trees as food for tree dogs, slender loris, birds, squirrels, flying foxes etc. The rest, we enjoy and share with friends.

10. There is a popular perception that non-human animal products are essential to sustain organic farming (eg. cow/goat dung for fertilizer). Do you agree with that?

No, we wholeheartedly disagree. And it is scientifically incorrect. Instead of trying to reinvent the spoon, we can refer to this article: http://www.stockfreeorganic.net/category/whatandwhy/

11. What, in your opinion, could be the best way to help people embrace a vegan lifestyle?

That is a huge question. And the simple answer is that a lot of people are not aware of the cruelty to animals that they are responsible for by consuming animal products. They should probably be shown what actually happens to farm animals. They should experience and taste an abattoir. It would definitely help some people embrace veganism. Others have already connected the dots, but may be struggling with producing healthy and tasty vegan meals. Local vegan groups could reach out, create cooking courses etc. to help these. But, unfortunately, the vast majority of humans are not sufficiently interested in removing or alleviating the suffering of animals. And the number of killed and suffering animals is increasing year on year with the increase in human populations and the increase in the number of relatively affluent people. We are, as you can see, not particularly optimistic about the future. We do, however, think the introduction of cultured or synthetic meat can have a huge positive impact. In fact, it may be the only realistic way to actually reduce animal killing and suffering.

Thank you very much, Morten, for the enlightening replies. We are confident that your lifestyle will be a huge inspiration for many.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

About the authors:

Dr. Arun, a lacto vegetarian for most of his life, has been a vegan since 2007. He became one after his vegan brother, Balaji showed him how the dairy industry exploits cows. He is one of the trustees of Samabhava, an equine welfare organization.

Uthra is a freelance fashion designer, who began her journey to veganism in April 2013. She loves to cook, and impresses her neighbors and relatives with sumptuous, flavorful, and appealing vegan dishes. Some of her recipes (including the vegan gulab jamoon) are shared at

her blog https://uthradeviarun.wordpress.com. Together, Uthra and Arun are experimenting with a veganic micro-garden nourished with compost from their vegan kitchen by-products and are seeing fairly good results.

I am vegetarian turned vegan. I was looking for vegan restaurants in Kerala when I saw your article. It is very nice to see other people who understands about animal exploitation.

Charutha, it is wonderful that you have turned vegan. Traditionally, Kerala cuisine has a number of naturally occurring vegan delights, doesn’t… especially the Payasam uses coconut milk and is so delicious. If you are used to coffee, coconut milk really goes very well in coffee!